THE INDEPENDENT, ED CUMMING, 28 SEPTEMBER 2020

***** 5 STARS

There are no frills whatsoever to this doc about the 1970s and 1980s contaminated blood scandal – but that only makes it hit harder.

The documentary director Marcus Plowright was recently nominated for a Bafta for 2019's The Murder of Jill Dando, a patient and gripping examination of a killing that shook the nation. With In Cold Blood (ITV), he turns his attention to the contaminated blood scandal, another decades-old front-page story whose memory has faded with time. Blood treatments given by the NHS during the Seventies and Eighties infected at least 1,300 people with HIV and 4,000 with Hepatitis C.

Over 1,500 have died.The film’s title, irresistible given the subject, invites comparisons with Truman Capote’s true-crime book of the same name. Where that was a study of a Kansas killing spree, this is a story of institutional malpractice and alleged cover-ups, a scandal with thousands of victims, many perpetrators and which will most likely never be truly resolved.The film is based on the work of Jason Evans, a campaigner whose father died of Aids after receiving contaminated blood products. As he points out, the death toll from the scandal is greater than Hillsborough, Grenfell and all the terror attacks on British soil combined, but with nothing like the same public awareness. In France and Canada, health officials were eventually jailed, but while the British government has made payments to some of the victims, nobody has ever been held accountable. Yet, as is clear from the film, patients continued to receive Factor VIII long after suspicions were first raised. In subsequent investigations over the years, it has been discovered that crucial documents were destroyed, often around the same time as information came to light about who knew what when. It was only in 2017 that Theresa May finally ordered a public enquiry, which reopened this month.

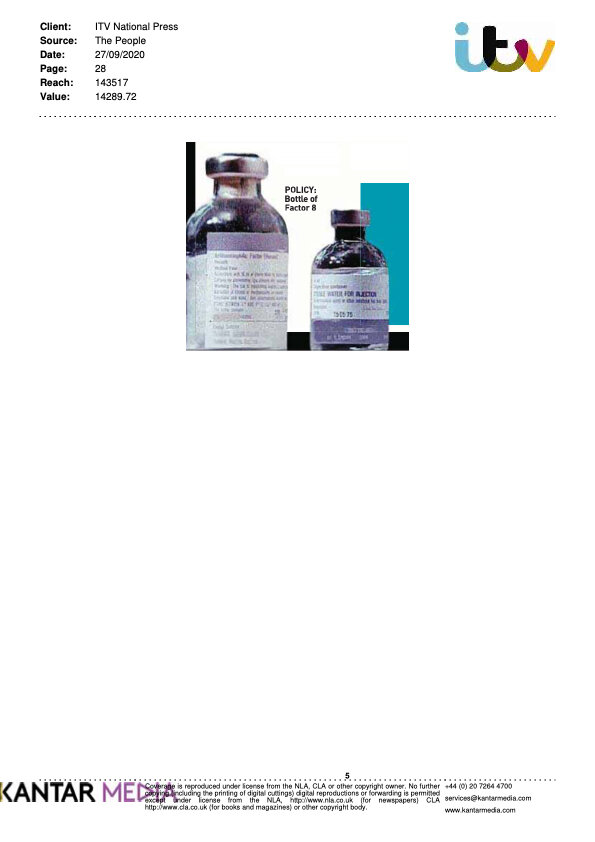

Forty years after most of the infections took place, there is a lot of ground to go over. For many years, Britain’s thousands of haemophiliacs thought Factor VIII was a wonder drug. They could keep it in the fridge and inject themselves to help control their bleeding, with no need for doctors or hospitals. As the drug’s popularity soared, the NHS started importing Factor VIII from America. The treatment was made from concentrated plasma, so each batch contained blood from many thousands of donors. American donor standards were less rigorous. Blood infected with hepatitis, and later HIV, made its way into the supply chain. Warning bells were being sounded as early as 1983, but as documents show, NHS officials were slow to respond to the threat. There’s a special terror in the thought that the blood you are injecting as a cure might contain an even worse illness.

The Times, James Jackson, 28th September 2020

**** 4 STARS

This week a public inquiry into the infected blood scandal reopens, and it would be unfortunate in the extreme if it were overshadowed by the Covid crisis. Let’s hope that In Cold Blood, Marcus Plowright’s damning film, spanning decades of malfeasance, will help that to not be the case.

It may be three decades since British haemophiliacs were given plasma infected with HIV and hepatitis C — killing thousands and hitting the lives of thousands more — but the depth of the scandal is still coming to light. The dogged work of the campaigner Jason Evans, who lost his father to HIV/Aids as a result of contaminated blood, has turned up numerous “destruction receipts” in Department of Health files about the safety of blood — suggestions of a possible cover-up that would be, frankly, criminal.

While this was a film full of dignified fury, its success could be measured by how much anger it induced in the viewer. I’ve seen few documentaries that have made me angrier.

THE TELEGRAPH, ANITA SINGH, 27 SEPTEMBER 2020

****4 stars

The infected blood scandal is recognised as the biggest NHS disaster in history. You may be old enough to remember the story breaking in the 1980s. This newspaper has carried coverage over the years. At least 1,500 victims have died. In Cold Blood (ITV), a documentary timed to coincide with the reopening of an official inquiry, contained the horrifying statistic that the infected continue to die at a rate of one every four days. Yet the case does not have the nationwide recognition of other British tragedies, and many victims feel they have been forgotten. Is that because the case has dragged on for so long, with no one prepared to accept the blame? Or because the victims were tainted in those early days by the stigma around Aids?

For those unfamiliar with the details, the documentary laid them out. In the 1970s, the NHS began prescribing factor VIII, a new treatment for haemophilia. The clotting agent was seen as a wonder drug, improving the lives of patients because it was so easy to use: a little bottle kept in the fridge, self-administered via an injection to the back of the hand. But as demand rapidly outstripped supply, the Department of Health made the decision to import factor VIII from the US, where people from high-risk groups were paid to donate plasma. Thousands of these donations were pooled to make batches of the drug; it took only one donation tainted with HIV or Hepatitis C to infect hundreds or thousands of vials.

What followed was a staggering account of a cover-up, much of it unearthed by Jason Evans, whose father was infected and later died. His dogged investigations uncovered document after document which showed that the fatal risks of factor VIII were known to the authorities long before they were made public. One doctor from a haemophilia centre recalled sending off samples for HIV testing after the news filtered out. “Thirty-five brown envelopes came back. I opened them one by one, and all but one of them were positive.” A number of his patients were children.

It was a heavy-going 90 minutes, but throughout you could feel that the programme-makers (led by award-winning director Marcus Plowright) took very seriously their responsibilities to the victims and families. Many were featured here, including the parents of Lee Turton, who was infected, like many, with both HIV and Hepatitis C. They vividly recalled the gut punch of hearing the news, and Lee saying how scared he was. Only late in the film did we discover that Lee was just four years old; he died aged 10. It was impossible to watch without feeling a cold fury. Let's hope that the inquiry will, at least, bring these families some justice.

PREVIEWS

The Times

Kaya Burgess 22 September 2020

Tainted blood scandal: Officials ‘knew of hepatitis risk from US blood in 1980’

New evidence has emerged that health officials were aware of the risk that blood products imported into Britain from the United States were contaminated with hepatitis and HIV years before they were withdrawn from use on the NHS.

The contaminated blood scandal led to the deaths of more than 2,400 people and thousands more were infected with one or both of the deadly viruses through NHS treatment in the 1970s and 80s.

The Times has seen memos sent by officials within what was then the Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) showing that the risk of hepatitis in American blood products was known as early as 1980, while the risk of HIV was known in 1983.

However, the government said that there was no “conclusive” proof of a link and the use of infected products on the NHS continued well into 1985 when they were replaced by products treated in a way to kill viruses. Most of those treated have said they were never told of any infection risk.

Thousands of haemophiliacs were infected through a clotting agent called Factor VIII, largely created from blood given by American donors. In the US donors were paid, leading drug users and prostitutes, groups with a higher risk of blood-borne infections, to donate in large numbers.

Up to 25,000 people in Britain may have been infected and one victim still dies every four days.

The infected blood inquiry restarts today to uncover when the government became aware of the risk and whether they could have acted sooner to withdraw potentially infected products.

In early 1982, doctors noted that haemophiliacs had started dying of Aids. By 1983, this had been linked to Factor VIII.

An article in The Guardian in November 1983, headlined “US blood caused Aids”, cited a study in The Lancet, stating: “The British haemophiliac who died from Aids almost certainly caught the disease from contaminated supplies of the blood-clotting agent Factor VIII, imported from the US.” An ITV documentary called In Cold Blood, to air next Sunday at 10.20pm, will show that a copy of this article was sent to Dr Diana Walford, then a DHSS official.

A note from an unnamed civil servant asked her: “Is it ok for us to continue to say: ‘There is no conclusive proof that the disease has been transmitted by American blood products?’”

A handwritten reply from Dr Walford noted: “Thanks. Yes it is ok.” In that same week, Ken Clarke, now Lord Clarke of Nottingham and then a health minister, also told MPs that there was “no conclusive evidence”. Dr Walford confirmed in 2011 that the note was in her hand.

She told the Penrose inquiry, a private inquiry in Scotland to examine the scandal, in 2011: “Given the state of knowledge about Aids and its causative agent at that time, this was the appropriate answer.” A government document from 1987 states that it was “strictly true” to say this, as conclusive evidence only came in April 1984 “when the AIDS virus was isolated”.

An earlier letter from Dr Walford in 1980 stated that it was important to prevent the contamination of “UK material with imported hepatitis viruses”, adding that health officials were aware of “post-transfusion [and blood-product infusion] hepatitis in the USA [which] can be rapidly fatal”.

Jason Evans, the campaigner whose father died as a result of the scandal, said: “There was clearly more than enough evidence [to withdraw the products]. It felt like everyone knew [about the risk] except the people receiving Factor VIII, and that can’t be right.”

Dr Walford has never spoken in detail about the scandal. She told The Times yesterday that she would be “happy to assist” the inquiry and provide “a full account of events”, but declined to comment further as the inquiry is “the proper forum for me to discuss those events and my involvement in them”.

The Department of Health and Social Care has been co-operating with the inquiry, describing the scandal as a “tragedy”.

The inquiry will hear from Lord Owen, health minister from 1974 to 1976, today. He is expected to discuss his unsuccessful attempts to end Britain’s reliance on imported blood products and his suspicions that key documents from his time in office have been destroyed.

The Times, Kaya Burgess, 22 September 2020

Tainted blood scandal inquiry reopens

Evidence has emerged that health officials were aware of the risk that blood products imported into Britain from the US were contaminated with hepatitis and HIV years before they were withdrawn from use on the NHS.

More than 2,400 people died and thousands more were infected with one or both of the deadly viruses through NHS treatment in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Times has seen memos sent by officials within the health department showing that the risk of hepatitis in American blood products was known as early as 1980 and the risk of HIV was known in 1983. The government said, however, that there was no "conclusive" proof of a link and their use continued into 1985. Up to 25,000 people in Britain may have been infected and one victim still dies every four days. The Infected Blood Inquiry restarts today to uncover when the government became aware of the risk and whether it could have acted sooner.

The Guardian, Owen Bowcott - 21 September 2020

Infected blood scandal: Treasury refuses to publish key documents

Response to FoI request from victim’s son says disclosure may attract ‘disruptive’ media coverage

The Treasury is refusing to publish key documents about the treatment of haemophiliacs infected by the NHS with HIV on the grounds that it would be “disruptive” and material might be “distorted” by the media.

The unusual reasons cited by officials for refusing a Freedom of Information (FoI) request have emerged before a new round of public hearings at the Infected Blood Inquiry

Jason Evans, whose father died after receiving contaminated blood and founded the Factor 8 campaign, has been an effective and energetic excavator of hidden Whitehall files.

Nine months ago he asked for further pages from a file dating back to 1989 entitled Haemophiliacs with AIDS/HIV: Macfarlane Trust and Social Security. The Treasury released pages 1-35 of the file last year.

Evans sent eight further letters and appealed to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) before he received a reply. Most files of that era should by now have been released to the National Archives in Kew and be available to view.

In their eventual refusal letter, the Treasury said some of the material covered “personal data of living individuals” and some would “prejudice the administration of justice”. It said the material had been handed over to the inquiry.

The letter finished: “We consider that the piecemeal disclosure of material and the consequent media coverage that it attracts is disruptive to the proper workings/process of the inquiry itself.

“Where information already held by, and under consideration by, the inquiry is released under the FoI Act, there is a real risk of that information being quoted from selectively in the media, with the result that the roles of particular individuals, their decisions and actions may be presented in a distorted way.”

Evans told the Guardian: “It’s outrageous that the government won’t disclose files to me concerning what happened to my father because, basically, they are concerned I might show those documents to the press.

“Yes, there is an inquiry going but it’s not a court case. It’s 30 years overdue ... All of the families affected by this deserve transparency and not withholding of information because of what the press may report.

“If the Treasury doesn’t send me these documents by the end of the week, I’ll have no choice but to lodge another challenge against them with the ICO ... It’s not acceptable ... to hide information because they’re scared of the media. I thought this was supposed to be a country that stood by freedom of the press?”

Des Collins, a partner at Collins Solicitors who represents more than 1,400 families infected and affected by the contaminated blood scandal, said: “Our clients are very concerned that this may be the beginning of yet another cover-up some 40 years after the first and they are determined not to let that happen.

“The Treasury’s response to what is on any basis a good faith request is, to say the very least, disappointing. We have every right to expect the government’s transparency pledge to all those affected by the contaminated blood scandal to be upheld.

“This unwillingness to disclose the requested files does beg the question as to their contents and also whether the government is genuinely committed to transparency.”

The infected blood inquiry, set up in 2017, reopens in London on Tuesday. Its hearings will be broadcast live online.

The inquiry is examining how as many as 30,000 people became severely ill after being given contaminated blood products, imported from the US, in the 1970s and 80s; about 3,000 haemophiliacs have since died.

The first witness will be Lord Owen, who was health minister from 1974 to 1976. He has alleged that maladministration by his former department contributed to the scandal and questioned why a promise he made – that Britain would become self-sufficient in supplies of clotting factors – was not fulfilled.

A spokesperson for the inquiry declined to comment on the FoI refusal or whether the inquiry was consulted.

A Treasury spokesperson said: “It’s important that those affected by this tragedy get the answers they deserve and lessons are learned – which is why the independent inquiry has been established.

“We’ve been fully transparent and supplied the inquiry with all relevant files, including the specific information referred to here.

“But it’s important the inquiry can carry out its responsibilities effectively and be able to dictate the timetable for consideration and disclosure to the public of any records or information.”